The Japanese beetle (Popillia japonica) belongs to the Scarabaeidae family (scarab beetles), and originally comes from Asia (Japan, northern China, the Russian Far East). It was introduced to North America at the beginning of the 20th century and causes considerable damage there (to the tune of several 100 million US dollars annually). In Europe, the beetle was first discovered in the Azores in the 1970s, and on the mainland for the first time in 2014, in Italy near Milan. It is thought to have arrived there by plane, and has ultimately been able to spread further from there.

The Japanese beetle spreads mainly through its transport with the movement of goods and people, sometimes also through the reconnaissance flights of a few individual beetles. Mass flights have also been observed.

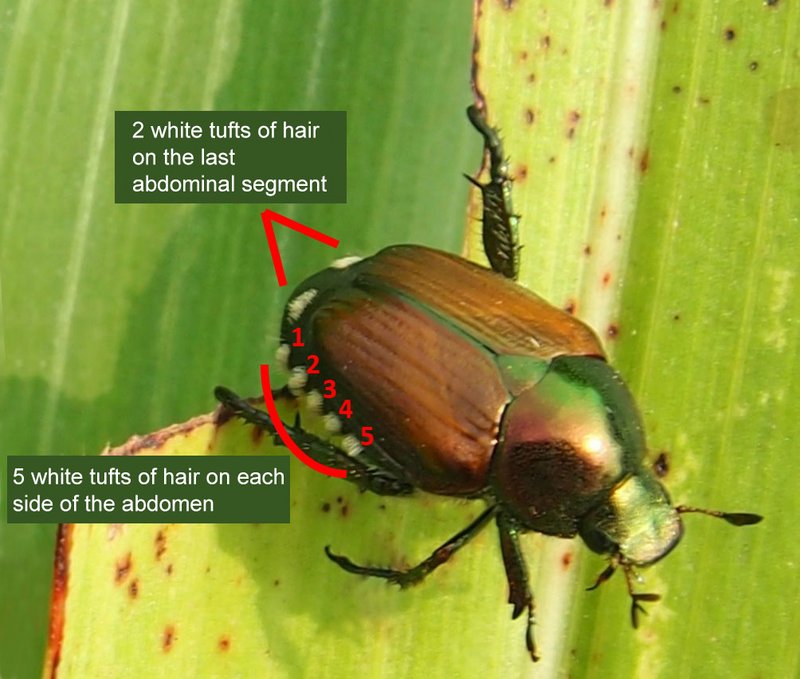

Appearance and possible sources of confusion

Adult beetles are 8–12 mm long and 5–7 mm wide. They are similar in appearance to our native Carabus hortensis beetles. Unlike them, however, the Japanese beetle has five white tufts of hair on each side of the abdomen and two white tufts on the last abdominal segment, as well as a striking, metallic green-shimmering neck shield (pronotum, fig. 3). The elytra are brown and do not completely cover the abdomen.

The Japanese beetle is sometimes confused with native beetles - most commonly with the June beetle (also known as garden chafer or garden foliage beetle, Phyllopertha horticola). This beetle has no white tufts of hair, however.

Biology

The Japanese beetle usually needs one year for its development from egg to adult beetle. In cooler regions its development may take up to two years. In Switzerland a development period of one year is assumed.

The eggs, which are approximately 1.5 mm in diameter, are transparent to creamy white. They are laid up to 10 cm deep in the soil, usually in groups of 2-4 eggs.

The young larvae hatch from the eggs laid in the moist soil approximately two weeks later. They are initially not very mobile, and they feed on plant roots. In late autumn, the grubs in the third larval instar retreat to deeper soil layers (25-30 cm deep and frost-free) to hibernate. As soon as the soil temperature rises above 10°C in spring, the larvae migrate back into the upper soil layers (2.5–10 cm deep) and start feeding on the roots again.

The cream-coloured larvae of the Japanese beetle are typically c-shaped grubs (fig. 7), with distinct pairs of legs in the chest area and a dark-coloured head capsule with strong mouth tools. The bristles arranged in a V-shape on the rearmost abdominal segment (fig. 8) clearly distinguish them from other grubs.

The three larval instars:

| L1 | white, 1.5 mm long, legs from thoracic area | |

| L2 | 1.9 mm wide and 2.2 mm long head capsule | |

| L3 | 3.1 mm wide and 2.1 mm long head capsule |

The larvae pupate after four to six weeks. The initially light-coloured pupa (14 mm long and 7 mm wide, fig. 9) darkens in colour as it metamorphoses into a beetle. The adult beetles hatch between May and June. They start mating immediately. Adult animals live for 30 to 45 days.

The main flying time of the Japanese beetle is between the end of May and (the end of) August. The females lay between 40 and 60 eggs. This involves repeated mating and subsequent ovipositing. The perfect soil for oviposition has a medium to high soil moisture content.

The natural dispersal of the flying beetles is between three and 24 kilometres per year, with a daily radius of around 500 metres. The animals are attracted by plant excretions, among other things.

Host plants and damage

With over 300 known host plants, the Japanese beetle has the potential to threaten a wide range of plants and habitats. Adult beetles are to be found on a variety of forest trees, garden plants or agricultural crops, where they feed on the leaves, flowers and fruit. These include: maple, alder, chestnut, birch, hazel, beech, oak, plane, poplar, willow, lime, elm, larch and, among cultivated plants, especially apple, stone fruit, persimmon, grape vines, maize, soya, strawberries, blueberries, bilberries, blackberries, raspberries and strawberries, wisteria, hibiscus, asparagus, rhubarb or roses.

Fig. 10. A vineyard near a wooded area - ideal living conditions for Japanese beetles. Photo: Doris Hölling

Early summer damage to trees such as alder and hazelnut can be found immediately after the beetles hatch, before they move into the vineyards to feed on leaves or to mate.

In autumn, the beetles are often found on common loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria) or red clover (Trifolium pratense) – plants with purple/wine red flowers. The beetles do not fly to neighbouring clover plants with white flowers, for example. These plants are found in the more moist areas next to the areas planted with vines and in the areas bordering on forests or rows of trees.

The larvae prefer to feed mainly on the roots of grasses on damp meadows or lawns. However, they are also found on the roots of cultivated plants. In Italy, for example, damage has been observed on seedlings of raspberries, maize, oilseed rape and rice.

Both larvae/grubs and beetles cause damage to numerous plant species. This is already very well documented for the beetles. Above ground, they damage the leaves (skeletal feeding) and fruits (various berry shrubs, plums, nectarines, apricots, apples, persimmons) of their host plants, where they are often found in masses.

It is more difficult to determine exactly which plants the larvae favour, as they cannot be seen feeding. Damage to plants is caused by grubs in the soil feeding on the plant roots. These feed mainly on grass roots, but also on the roots of maize, soya, tomatoes or strawberries. The root feeding of the larvae leads first to the undersupply, and later to the interruption of the supply of water and nutrients. The plants become less resilient. This leads to reduced harvests and even crop failures or the death of the plants. Root feeding on damp meadows or watered lawns (golf courses, football pitches, parks or lawns in gardens, or on racecourses, as recently in San Siro in Milan) leads to the development of brown, dried-out patches.

After rainy summers, there is an increase in the population density of the beetles in the following year, while very dry years lead to a significant decline in beetle numbers.

Adult Japanese beetles often gather in large groups on the food plants and eat their way down them from top to bottom. It is striking that some individual plants are completely stripped, while neighbouring plants are spared. The feeding damage occurs above ground on leaves, fruits and flowers. Irregular traces of frass can be found on petals and fruits.

Examples of feeding damage on various plant species

How the beetles spread through transport

The beetles are mainly transported over long distances from infested areas by vehicle or means of transport (i.e on trains, postal vans, lorries, or with goods transport (e.g. rolled turf, soil transport, plants, fruit deliveries, green waste), as well as by commuters or tourists, who unwittingly carry the beetles as “stowaways”. They can be carried in/on cars or coaches, on clothing, or in camping equipment, rucksacks, camera bags or with imported plants - for example roses from infested areas. Anyone visiting an infested area can thus unknowingly contribute to the spread of the pest – and this must be prevented at all costs.

In Switzerland, Japanese beetles have been discovered in fruit shipments (berries, table grapes) from abroad. With the consignments of fruit, the beetles can quickly be transported to new, previously infestation-free areas. Berries that are harvested and dispatched during the beetles’ reproductive season pose a particular risk for the introduction of the pest. The table grape season tends to be at the end of the beetle's development period, so the risk of damage caused by released insects from consignments of grapes is considered less by international experts.

Prevention and control

Where large irrigated areas are available, especially permanently irrigated areas, countless larvae are to be found. In non-irrigated cultivation areas, on the other hand, only a few larvae are found, as the development conditions there are not ideal for them. The females of the Japanese beetle select breeding sites with a high degree of soil moisture in which to lay their eggs, to ensure good starting conditions for the eggs and larvae.

Automatic irrigation of turf or lawns in stadiums, at outdoor swimming pools, in gardens, on football pitches or lawns in parks or on campsites is thus a major problem, as the beetles can develop there both easily and unnoticed. They only become noticeable when lawns die as a result of them feeding on the roots or when the beetles infest other plants in the vicinity.

During the main flight season of the Japanese beetle, the watering of football pitches, golf courses, lawns in parks and private gardens should be avoided. It is especially important to dispense with the watering of lawns in infested areas, as watering creates perfect conditions for the beetle larvae.

In Switzerland, no special insecticides are currently approved for use against the Japanese beetle for control purposes as they are for example in the USA against both the larvae and the beetles. Some biological control agents seem promising, such as parasitic nematodes, or entomopathogenic fungi or bacteria, which can be deployed to control the larvae of the Japanese beetle in the soil.

Birds, ground beetles, shrews and moles are natural antagonists that also help to keep invasive pests in check in this country. They cannot eradicate the beetles, however.

In endangered areas, traps with pheromones (sexual and plant attractants) can be set up. Host plants or the soil should also be inspected visually on a regular basis. In Switzerland, any suspicious signs or beetles should be reported immediately to the responsible Cantonal Plant Protection Service. If they confirm an infestation, an infested area and a buffer zone are designated. The Plant Protection Service can control isolated populations by mass trapping with attractant traps. In the case of infestations over extensive areas, as in Ticino/Tessin, the measures to be taken are regulated in a “General Ruling”. Unauthorised mass trapping, for example by garden owners, should be avoided at all costs!

As the beetles are easily recognisable, mechanical collection of the insects can help at the beginning of an outbreak. This is most likely to be successful early in the morning or late in the evening.

A higher grass-cutting height can also counteract the spread and reproduction of the beetles. In early autumn, mechanical tillage of the soil can massively reduce the survival chances of the larvae, which feed close to the surface - this also applies in gardens!

Soil transport poses a great danger, as larvae in the soil can be carried to unaffected areas in this way. The same applies to rolled turf. Beetles can also be transported with green waste.

Public relations work is particularly important, to make sure people know what must be avoided at all costs to prevent the further spread of this invasive species .

How to avoid accidentally introducing this pest, where to get support, and where to report findings of the Japanese beetle:

Translation: Tessa Feller

![[Translate to English:] [Translate to English:]](/assets/_processed_/6/0/csm_wsl_alb_europa_weiss_e3f367e50a.jpeg)