As in Bavaria, it is noticeable at European level that forest education has made considerable progress. It began originally with “classic” forest tours. Foresters wanted to motivate people to experience the forest, using new, livelier and more motivating methods and approaches tailored to the needs of the relevant target group. And one key objective from the outset was to appeal to the participants' sense of responsibility and perception of values in the context of forest-related issues.

Review: ESD and shaping competences are gaining in importance

Every year since 2005, the forest education subgroup of the Forest Communicators Network (FCN) “FCN Subgroup Forest Pedagogics” has organised a European-wide, highly practice-oriented specialist congress. They have developed an action plan for forest education, aimed at strengthening the status of forest environmental education. One important objective of the plan is to ensure the quality and development of forest education programmes. Prompted by the “UN Decade of Education for Sustainable Development (2005-2014)”, Bavaria, Austria and Switzerland in particular provided the impetus for also integrating ESD objectives in forest education. What is meant by ESD is an education that enables people to think and act in a sustainable way. It is intended to enable each individual to understand the impact of their own actions on the world. According to the UN goals, sustainable development should be anchored as a guiding principle in all areas of education, so that global problems such as climate change, poverty and the overexploitation of nature can be solved. It is self-evident that forest education can and must make a valuable contribution to this.

As a result of the UN Decade of Education for Sustainable Development, forest education in Bavaria was initially strongly geared towards the three “ecological - economic - socio-cultural” dimensions of sustainability. In the “Forest Education Guidelines”, information was for example added for each activity, indicating which of the three dimensions could be given particular emphasis with the activity in question. The more detailed objectives of the German UNESCO Commission - in particular the 12 shaping competences (participation skills) outlined by de Haan - soon also became important for the objectives of forest education in Bavaria. The Bavarian Forestry Administration’s “Forest Education Guidelines” (2017) set out these educational objectives as follows:

Forest management serves as a sustainability model that includes a balance of all three dimensions of sustainability (economic, ecological and socio-cultural). The shaping competence of the participants is to be promoted by creating learning situations in which

- the participants come into contact with nature and are given the opportunity to actively help shape it (participation),

- the participants are guided by a respectful and responsible approach to the natural foundations of life

- thinking in networks and farsighted thinking and action are encouraged; local, regional and global interdependencies are recognised; and

- solutions can be developed on the basis of current and real problems.

The ESD objectives have been incorporated in all training modules in the further training programme leading to a “State Certificate in Forest Education”, and also serve as important assessment criteria for the examination of participants. With regard to their understanding of ESD, the FCN subgroup has agreed on the “Step-by-step model - six pedagogical steps to environmental maturity”, as developed by the Norwegian Forestry Extension Institute (Figure 4).

Status quo and focus on the UN's 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development

Many well-trained forest educators in Europe can quite rightly claim that their programmes already fulfil the first four stages of this model: They convey the joy of experiencing nature, allow people to experience nature directly, and promote self-discovery learning. And when the forest - as a place of learning - and its responsible management - as an ingenious model for a comprehensive understanding of sustainability - can be “grasped” both literally and figuratively - level 3 and 4 are also achieved. Participants recognise interdependencies in nature and begin to understand the interactions between humans and forests. And forest education is thus already making a valuable contribution to ESD. Of course, forest education must still rise to the challenge and “climb” to the higher levels of Education for Sustainable Development (ESD). In Germany, Switzerland and Scandinavia in particular, many actors or projects already offer opportunities for decision-making and co-determination (step 5), or encourage people to take on concrete responsibility, or to grow in their sense of responsibility (step 6). The FCN subgroup is currently also discussing whether and how forest education should approach the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the United Nations’ 2030 Agenda - in particular the new goals, which are now categorised in terms of 17 global issues and no longer according to shaping competences (participation skills). SDG No. 4 “Education” is particularly relevant for forest education work, but almost all of the 16 other SDGs also contain sub-goals with references and links to forests or forestry. This abundance of goal systems is a real headache for many forest educators.

It also seems important for forest education programmes not to be measured by whether they address all of the 12 ESD shaping competences or tie in with as many SDG goals as possible. The programmes offered by forestry stakeholders in particular must not be allowed to lose their (forest) grounding. After all, there is growing interest in the situation of our forests throughout Europe, and the demand for forest tours with local and genuine forestry experts is also increasing. In addition, even “basic programmes” at levels 1-2 or levels 1-4 (Figure 4) can teach important “shaping competences” in the emotional, cognitive and social areas.

Forest education - ways forward

The old proverb “Let the cobbler stick to his last” (more modern version: “Never change a running system”) and Henry Ford's phrase “If you always do what you always did, you will always get what you always got” may thus all apply to the future of forest education. To put it another way: Not every change is an improvement - but there is no improvement without change.

It is undisputed that forest education must also break new ground and rise to current challenges. Throughout Europe, it faces similar social, forest political or forest-related changes, some of which are taking place very rapidly. And changes always lead to new opportunities.

This is described below in a total of six theses, and six opportunities resulting from them for sustainable forest education:

Thesis 1: The focus is on the forest - both in public discourse and as an issue with a high level of political relevance. The forestry industry is under pressure. Native tree species are displaying extreme levels of damage in some regions. Climate change requires sustainable guidelines for forest restructuring and modern management concepts.

Opportunity: These challenges can only be solved through dialogue among representatives of the forestry administration, forest owners, other forest interest groups, and society. Forest education programmes can play an important role here, bringing forest stakeholders into conversation with a wide range of interest groups.Thesis 2: Forests, especially managed forests, store carbon in the long term. The sustainable use of wood as a raw material conserves resources and can help reduce CO2 emissions.

Opportunity: Acceptance of and understanding for sustainable forest use can be promoted through forest education programmes. Forest-related environmental education can also play a role in communicating the positive contributions of forestry to climate protection.Thesis 3: Society's view of forests and forestry is often characterised by alienation from nature, combined with great, often highly emotional concern for the protection and preservation of our forests. Forestry management is often perceived as presenting a threat to the forest. At the same time, people are increasingly interested in ecological issues.

Opportunity: Forest education can have an influence on strongly emotional, personal and subjective views of the forest and forest utilisation, or on views based on inadequate knowledge. Only those who are aware of the diversity of the ecosystem services provided by forests and their importance in the context of climate change can make a purposeful commitment to the interests of forests. Because forests are threatened by climate change, but they are also part of the solution.Thesis 4: More and more people are now visiting the forest for its effects on their health and well-being. As well as the lasting trend in forest bathing, the Covid pandemic has also encouraged the search for recreation in the forest.

Opportunity: Forest education programmes can not only help make the growing number of forest visitors “mindful” of their own well-being, but can also encourage them to be “mindful” of the needs of the forest.Thesis 5: Teenagers and young adults in particular want to assume more responsibility for environmental issues and play an active role in shaping the future of our planet. Today’s committed, highly motivated teenagers and young adults will be the social and political decision-makers of tomorrow - in just a few years’ time.

Opportunity: Forest-related educational programmes can offer young people incentives for their own actions. This can and must go beyond tree-planting activities to enable self-discovery, research and recognition, as well as participation in forest-related decisions.Thesis 6: Schools and the education sector are increasingly looking for starting points and issues to make sustainability and climate protection easier to grasp and more understandable for learners.

Opportunity: The forest is an excellent place of learning and a model for sustainability issues. The effects and risks of climate change are more easily recognisable and understandable in the forest than almost anywhere else. Forest-related environmental education can discuss ways out of the climate crisis, and encourage a sustainable lifestyle.

The bottom line

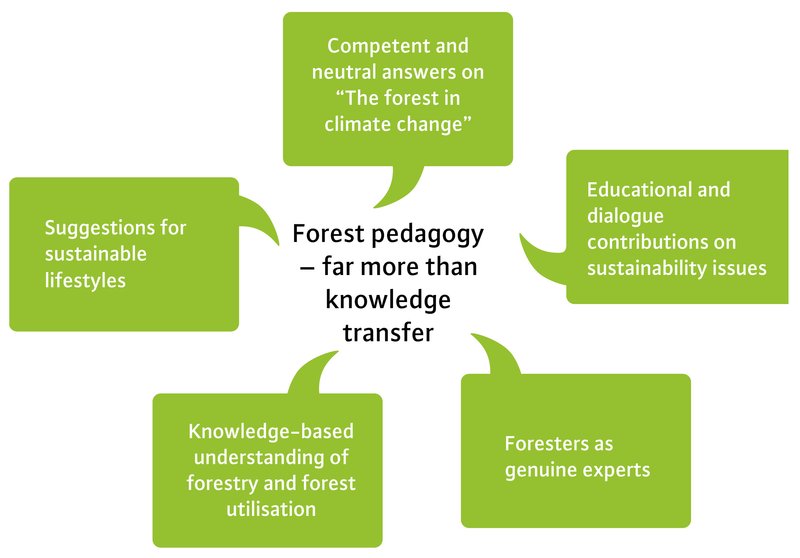

We must take advantage of these opportunities and implement them in forest education programmes. All forest educators can help do this in their programmes:

- by pointing out the relationships between climate, forest and society as well as lifestyles/behaviour

- by initiating learning processes that generate insight and stimulate changes in behaviour

- by creating understanding for forestry management and the responsible use of nature

- by ensuring that foresters continue to be perceived by society as responsible and competent experts and contact persons for the protection and utilisation of forests

Summary

Forest education has evolved continuously over the last few decades. What began with the classic “forest tour” to experience the forest has been supplemented and expanded over the years to incorporate ESD goals, shaping competences and SDGs. As a result, forest education has gained in importance and become more goal-oriented and more complex. This sometimes makes it more difficult for forest educators to remain competitive with their programmes.

Interest in the forest, the opportunities it offers us in times of climate change, and the risks to which today’s forest is exposed are growing in equal measure. As a result, the expectations placed on forestry education in terms of demonstrating interrelationships and teaching future decision-makers the necessary skills are also increasing. However, forest education programmes may not necessarily need to move very far from the classic forest tour, and they certainly do not have to be reinvented. In a nutshell: Never before has social dialogue on forest-related issues fallen on such fertile ground - and forest education has thus never been more important than it is today!