Anything but ordinary

The common ivy (Hedera helix) is anything but an ordinary plant. It is in fact exceptional in many ways:

- It is a relic of the Central European Tertiary - alongside holly (Ilex aquifolium) and boxwood (Buxus sempervirens)

- It is the only representative of the Araliaceae family in Germany; and is otherwise predominantly found in the tropics

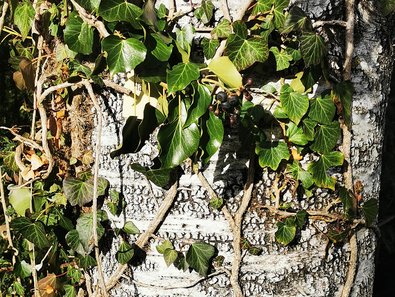

- It is the only native root climber in central Europe

- It is one of the few native evergreen shrubs

- It flowers in late autumn

- Its berries ripen over winter

- It forms two distinct leaf shapes (heterophylly; juvenile/adult leaves)

- It has different shoot forms (dimorphism): young shoots on the ground or climbing; and flowering, fertile adult shoots without adhesive roots

Distribution and habitat

In central Europe, ivy is a characteristic species of deciduous forests, growing from the plains to the submontane altitudinal zone. Its oceanic main distribution area is in the regions of Central Europe with mild, humid winters. The closed natural range of ivy in Europe extends from the Iberian Peninsula, Italy, Greece and Turkey northwards to the British Isles and south-east Scandinavia. The eastern edge of its range runs from the Baltic States via the Carpathians to the Black Sea. Ivy prefers nutrient-rich soils with a good water supply, but also colonises slightly acidic substrates. Ivy is now considered naturalised in the south-east of the USA, having been introduced there in 1750.

Profile of common ivy (Hedera helix)

Appearance: large-leaved, evergreen, shade-tolerant, hardy, perennial climbing shrub with alternately arranged green leaves; the leaf shape changes with age - from three-lobed to ovate; flowers are produced in umbels (September-October), fruits ripen in winter and spring.

Sites: Forests, ruins or quarries, also very common in urban areas, where the plant thrives on house façades, in cemeteries or in shady corners in parks.

Age: can live as long as 400-500 years. After about 10 years, ivy changes in appearance and reaches its mature form. The leaves that initially had 3-5 lobes then become unlobed and ovate. After approx. 20 years, the ivy bears umbel-like flowers and forms berries.

Uses: Used as a medicinal plant from antiquity to the present day (e.g. medicinal plant of the year 2010).

Caution: Fresh ivy leaves or juice can cause an allergic reaction on contact with the skin (allergic dermatitis). The berries are poisonous for children in particular, and cause diarrhoea, nausea and vomiting. Ivy is also poisonous for pets, including dogs, cats, rodents and horses.

Harmful for the tree or no problem?

Tree owners frequently ask themselves whether ivy is insignificant or in fact harmful for a tree. Opinions are quite divided here and prejudices persist. In this article, we aim to shed a little more light on the issue.

The “problem” is often not mentioned at all in the specialist literature, or the prevailing opinion is that ivy is harmless for most trees, and only poses a danger to a few. Although ivy can be a threat to some trees, this is not the rule - something which has also been shown by a number of scientific studies.

Trees supporting ivy tend to be large, stately trees with extensive crowns. Ivy leaves mainly appear where their exposure to the sun’s rays is greatest. This is important for the photosynthesis of the ivy plant.

Unlike tree parasites such as mistletoe (Viscum album), which take root directly on the branches of their host plants, ivy only uses trees to help it grow towards the light. The ivy roots on the trunk are adhesive roots. They only adhere to the bark of older trees superficially, and do not penetrate into the wood. Nor do they strangle the tree or take nutrients from it. In addition, ivy likes to grow in the shade of densely foliated trees with broad crowns.

The worry: that ivy may block out too much light

We must differentiate here between ivy on mature, large trees with mighty, spreading crowns on the one hand, and ivy on small or young trees on the other hand. Ivy can climb metres high into the crown of a tree.

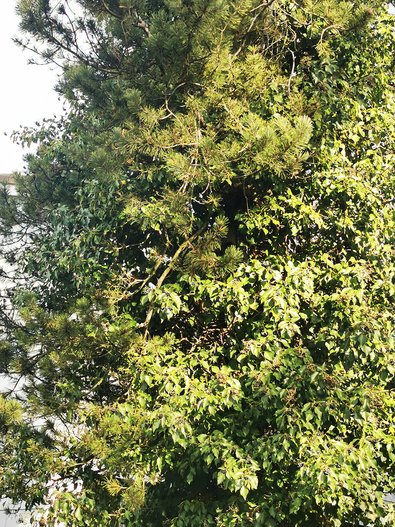

On large, stately host trees with spreading crowns, ivy grows up the trunk and sometimes into the crown, towards the sun. The host tree’s own photosynthesis takes place on the fine branches and at the sides of the crown. Ivy, on the other hand, grows mainly on the trunk and along thick principal branches. It thus rarely competes for light with the host tree.

The situation is somewhat different when it comes to smaller or young trees with less developed crowns, as the ivy can take over the entire crown in these cases, potentially leading to the death of the tree. Even after the tree has died, the dead snag remains as a supporting structure for the ivy for years to come. The sparser the crown of a tree is, the easier it is for the ivy to climb upwards. Dense crowns, on the other hand, cast a lot of shade, and slow down the growth of the ivy plant. Conifers are thus much less likely to be overgrown by ivy, as are deciduous trees with large crowns.

Shrub species such as hawthorn, which develop into smallish forest trees, or smaller tree species such as goat willow (Salix caprea) or silver birch (Betula pendula), can be damaged by ivy. Ivy may also threaten tree species with narrow crowns, such as pear (Pyrus sp.) or silver birch (Betula pendula), by blocking out the light. With large native tree species such as oak (Quercus sp.), ash (Fraxinus excelsior) or sycamore maple (Acer pseudoplatanus), the current state of knowledge is that they are unlikely to be damaged by light competition from ivy (BUND).

There is no evidence that ivy deprives the tree of light and air if it grows up the trunk.

The worry: that it might suffocate the host tree

Ivy only climbs healthy trees with dense foliage on sites with good light exposure. Ailing or weak oaks and birches, etc. have sparse foliage, offering ivy the light and space it needs to grow.

It is thus not the ivy plants but poor site conditions that cause the death of large trees like this. These may include a lack of soil moisture in the case of oak trees, or diseases such as mildew, or pests like the green oak moth (Tortrix viridana).

There is no evidence to suggest that ivy deprives the tree of light and air by growing up the trunk.

The worry: that ivy will strangle the host plant

It is often feared that the stems of ivy climbing a host tree may strangle it. Ivy usually grows up one side of the supporting trunk and does not wind its way around the trunk like other plants such as honeysuckle, which may well have a constrictive effect. In forests it is particularly likely that ivy will only grow up one side of tree trunks, as the light falls mainly from one side and the ivy plant thus grows up this side towards the light.

To prove that the ivy is constricting the host tree, its tree rings would have to be examined. However, in most cases where ivy is believed to have been strangling its host, this examination has not happened.

In cases where the constricting effect of ivy has been examined, a restriction of the trunk thickness growth has never been confirmed (BUND).

When ivy grows on a supporting tree for a long time, the intertwining branches may form a kind of corset and eventually put pressure on the tree bark. Occasionally, trees will encase the ivy stems like foreign bodies. This may reduce the stability of the host tree, as the thickness growth is not constant.

The worry: that ivy may draw water and nutrients from the host plant

Ivy's soil or nutrient roots serve to anchor it in the soil and supply the plant with water and nutrients.

Tree trunks are only used as a climbing aid for the adventitious (aerial) or adhesive roots, which serve to attach the shoots and thicker stems of the plant to the supporting tree. The plant forms these roots only in the first few years (juvenile form). These roots do not pose any great danger to trees, as they do not interfere with the tree’s vascular system. Very occasionally, young adhesive roots in contact with water or the soil can turn into nutrient roots. This enables them to grow in damp stone crevices or on dead trees. The roots may also creep into cracks in vital tree bark, growing towards the moist area inside.

Ivy thus does not extract nutrients from the trees; it is not a parasitic plant with adhesive roots. Where site conditions are poor, there may be some competition between the roots of the ivy and those of its host tree in the soil, as they are next to each other there.

Conversely, it has been shown that trees with ivy growing on them often grow better than trees without ivy growth in the area, as the ivy leaves contain hardly any substances that inhibit decomposition, and thus have a positive influence on the turnover of organic matter in the soil. In addition to this, the delayed shedding of ivy leaves in spring ensures a continuous supply of nutrients to the trees.

The worry: that the ivy may be too heavy for the trees

If ivy spreads extensively through the tree crown, the area exposed to wind and snow is increased. Tall and vigorous trees can easily compensate for the additional weight and increased wind sail. In 2006, a French monitoring programme in deciduous riparian forests showed that a greater risk only exists for shrubs and young trees in the shrub layer: the sail effect of ivy growth is higher in percentage terms the smaller the overgrown tree is. This means there is an increased risk of damage being caused by wind and snow.

On small, weak or previously damaged trees, the ivy's weight can also represent an extra static load if it gets out of hand, but not in large, stable trees with extensive crowns with no visible damage (Nabu Berlin).

Advantages and disadvantages of ivy growth on forest trees

Advantages of ivy growth:

Ivy provides a habitat for insects, as well as nesting sites and food for diverse bird and bat species - and the older it is, the more it has to offer.

- Ivy flowers late, and represents an important food source for insects such as beetles, bugs, butterflies, hoverflies, bees and wasps, especially given that there are only about 20 other plant species also flowering at this time of year.

- In addition to these species that feed on the ivy plant, there are also numerous hunting or parasitic insect species, which in turn increase the food supply for birds and bats.

- The berries ripen between January and April and serve as food for many (>17) bird species, including chiffchaffs, robins, redstarts, starlings, blackbirds, blackcaps and thrush species, seeing as berries are scarce at this time of year.

- Ivy covers trunks with an interwoven mesh that becomes more and more dense with age, thus creating well-protected, sheltered nesting opportunities. A study in a protected forest in Baden Württemberg found that common woodcreepers, blackcaps, blackbirds, song thrushes, wrens, chiffchaffs, goldcrests, long-tailed tits, wood pigeons and jays all used ivy for their breeding sites.

- Birds find plenty of well-protected cover in the ivy for roosting in winter.

- Almost 50 species of fungi can be found on ivy.

Ivy growth also protects the tree trunks of species such as common beech (Fagus sylvaticus) ash (Fraxinus excelsior) or hornbeam (Carpinus betulus) against sunburn (bark burn) by providing them with shade, especially when they have grown up in the shade of other trees and are suddenly exposed when these are felled.

Ivy growth can also protect the trunks from frost cracks in winter, as it moderates the effect of temperature fluctuations. (Baumpflegeportal.de; BUND)

Lignifying plants such as ivy store CO2. They can thus make a valuable contribution towards improving the climate and climate regulation in cities. They also release oxygen, which improves air quality.

Having more ivy in urban areas is good for both climate and insect protection.

Recent studies also highlight the importance of ivy as a bioindicator of climate change in central Europe. A significant increase in the amount of ivy in some places in recent years is interpreted as an indication of the increase in milder winters. As well as its vegetative spreading on the ground, where ivy is often protected from frost damage by snow cover, the increased spread of the climbing and tree form in particular can be interpreted as an indication of global warming, as frosts can cause more damage to climbing ivy than to the ground form.

Disadvantages of ivy growth:

- Trees covered in ivy are not easy to check during safety inspections. Weak points are less visible. This is not usually a problem in the forest, but it is a different matter in urban areas.

- If ivy grows on to the branches, the tree receives less light and branches can die off.

- Young, diseased trees could potentially be damaged by ivy growth.

- In winter, ivy can act as a snow trap, and the additional weight can cause branches to break.

Tree maintenance

- Do not allow ivy to grow into the crown. Instead, remove the shoots regularly before this can happen. This preserves the benefits of ivy and ensures the survival of both plants.

- It is better not to allow ivy to grow on young and weakened trees with bark damage if you wish to preserve them. Although the ivy roots do not penetrate the bark, there is a perfect climate for fungi underneath the ivy.

- If the crown of a tree does indeed become overgrown, the tree owner must decide between tree and ivy. If the tree is given priority, the ivy can be cut back at the base of the crown. It certainly does not have to be removed completely. In this way, the ivy can continue to fulfil its other important tasks in the ecosystem.

Caution should be exercised during intervention measures!

- If you decide to remove ivy from the trunk, it is important to bear in mind that tree bark formed in the shade of ivy is at risk of bark burn after its removal, and may be damaged by the sudden exposure.

- Severe pruning can in fact encourage growth.

- In some states or regions, there are laws prohibiting the removal of ivy without good reason and making such removal punishable, as the removal may for example have a negative impact on the breeding and nesting opportunities of protected animal species.

Fig. 11. Ivy does not flower until late autumn. Photo: Stanzilla/Wikipedia

Bottom line

The common ivy has a bad image that is undeserved! Many animal species and also humans can benefit from ivy, for example on urban trees or green façades. Although ivy may block out the light from smaller trees or make them more susceptible to wind damage, the concern that ivy could damage or even kill large, vigorous trees is unjustified, and would not be biologically plausible for the plant, either.

There are frequent reports of ivy causing trees to die off, but these are not really substantiated. Cause and effect are not documented and they are often mixed up in case reports. Systematic, statistically meaningful studies with defined methods are required to examine the effects of dense ivy growth – not random observations made without reflection. Such scientific studies have been carried out in England, France, Germany, Italy and Turkey, among other places.

Translation: Tessa Feller

Literature

Literature references can be found in the following list of references (PDF).