Deciduous and mixed deciduous forests are a particularly high-quality habitat for many bat species. Here, the two native oak species (Quercus robur and Quercus petraea) play an important role. Of all the native tree species, they not only harbour the highest number of insect species, but also the highest arthropod biomass. This makes oak forests excellent hunting grounds for many species of bat. In addition, the sparse crown structure of the oaks, with the wide spread of their main branches and large spaces in-between is favourable for insect-hunting. Since both oak species have a lot of crown deadwood at a comparatively low age and usually reach a high age - even in commercial forests - oak-rich deciduous forests also offer an above-average range of roosting possibilities - and often for many years.

These forests are valuable from both an economic and an ecological point of view. To protect them from large-scale, mass propagation of pests and widespread defoliation by feeding over extensive areas, areas particularly badly infested with the gypsy moth have been treated with plant protection products in recent decades. In this context, the possible negative effects on organisms that are not the target of the treatment measures have also been discussed again and again. Bats are one example of these “non-target organisms”. They feed predominantly on insects, and may thus be indirectly affected by the measures (or a lack of them).

Until now, little was known about the effects of such plant protection measures on forest bats. The “Pilot study on bat activity in Middle and Lower Franconian mixed oak forest stands affected to differing degrees by climate change” (ST 353) was thus carried out to find out more.

Methodological approach

Within the framework of the project, call surveys with batcorders were carried out in the following stand types in 2020 and 2021:

- Oak or mixed oak stands with no predisposition to defoliation by feeding: stands for which there was no prognosis of defoliation by feeding - hereafter abbreviated as "n" (zero area/no defoliation expected)

- Oak stands or mixed oak stands with a predisposition to defoliation by feeding, but with no use of plant protection products: stands that were within the range of stands where defoliation by feeding was predicted, but which were not treated - hereafter abbreviated as "k" (no treatment)

- Oak or mixed oak stands with a predisposition for defoliation by feeding that were treated with the plant protection product MIMIC® in 2020: stands that were within the prognosis range and the treatment range - hereafter abbreviated as "b" (treatment carried out)

For this, four study areas were selected at the beginning of 2020 in Lower and Middle Franconia, in focal regions for gypsy moths, where the three condition types listed above occur next to each other. Three to four batcorder sites were designated for each study area and condition type, at which calls were recorded for one night respectively each month between April and September in 2020 and 2021 (Figure 3). In order to determine the comparability of the stands and to be able to assess the habitat quality for bats, standard forest structure surveys were also carried out at each batcorder site. This made it possible to analyse the diversity, species composition and activity of the bats, and to relate them to possible influencing factors (especially pesticide treatment and forest structure).

In the selection of areas in 2020, the sample plots of type k (predisposition, untreated) were specifically selected in stands for which defoliation by feeding had been predicted, but no treatment was planned. In fact, the expected partial or complete defoliation by feeding did not occur in these stands - apparently due to the already advanced gradation and the cool damp weather in spring. There was thus no partial or major impairment to the vitality of the trees, and no dying off of trees in the stands. This fact must be taken into account in the further explanations and interpretation of the results.

High overall species diversity in all variants

In total, 13 different bat species could be clearly identified in the study and their presence thus unequivocally verified. These are the barbastelle bat (Barbastella barbastellus), the serotine or big brown bat (Eptesicus serotinus), the Alcathoe bat (Myotis alcathoe), the whiskered bat (Myotis mystacinus/brandtii), Bechstein's bat (Myotis bechsteinii), Daubenton’s bat (Myotis daubentonii), the greater mouse-eared bat (Myotis myotis), Natterer’s bat (Myotis nattereri), the lesser noctule or Irish bat (Nyctalus leisleri), the common noctule (Nyctalus noctula), Nathusius’ pipistrelle (Pipistrellus nathusii), the common pipistrelle (Pipistrellus pipistrellus) and the soprano pipistrelle (Pipistrellus pygmaeus). This means that more than half of the 22 species native to Bavaria can be found in the study areas. No significant differences were observed between the three stand types. In both years, the proportion of species that were recorded equally in all three variants is very high, at 92 % (2020) and 85 % (2021) (Figure 4).

Diversity and activity at the batcorder sites

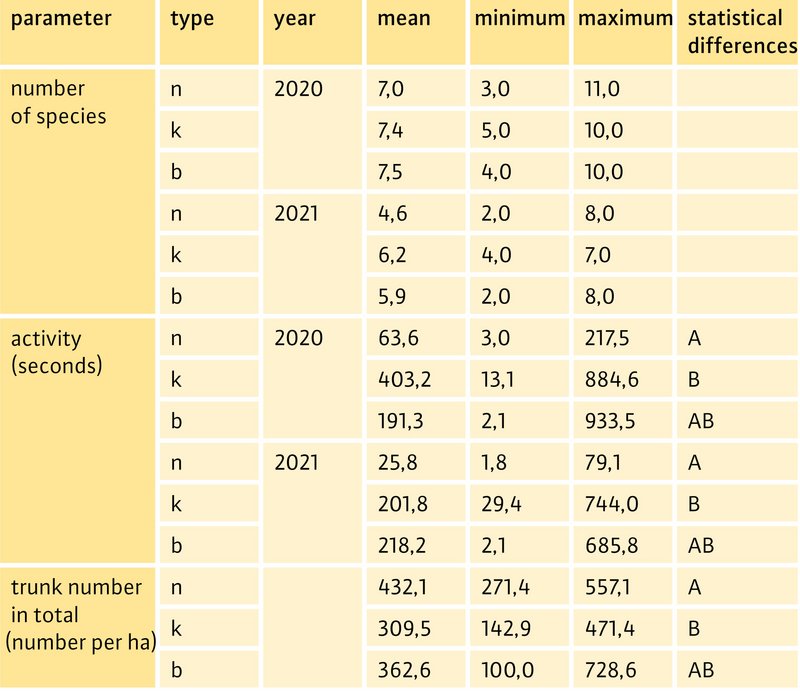

If we compare the three variants in terms of the number of species detected at the individual batcorder sites (alpha diversity), there were also no differences between the condition types. This applies both to the year of treatment, 2020, and the year after treatment, 2021. Overall, slightly fewer species tended to be recorded at the batcorder sites in 2021 than in 2020, regardless of the variant (Figure 5 above).

So while there were hardly any differences between the three variants in terms of species numbers, differences were evident in the level of activity (“seconds of activity”: duration of recorded calls in seconds as a measure for analysing the intensity of use of a site). If we compare the mean activity of all species/species aggregates, there are significant differences between the zero plots (type n) and the plots with predisposition but without treatment (type k) for both recording periods 2020 and 2021 (Figure 5 middle). The zero plots thus show demonstrably lower levels of bat activity than the non-treated plots. The plots of type b (treated plots) lie between the other two variants in terms of bat activity. They do not differ from them statistically. An effect of the treatment on the average total activity is thus not evident either for the year of treatment or for the following year. This also applies to individual species or foraging or hunting guilds.

What factors determine bat activity and diversity?

But why did the bats visit the zero areas less often and for less time? An answer to this question can be found by looking at the forest structures identified. Overall, there were hardly any differences in the forest structure between the three variants surveyed. This is for example true for the tree species composition, the stand age, the stratification, the amount of deadwood available or the base area of the stands - but not for the parameter “total number of stems per hectare”. The stand density on the zero plots (type n) was thus significantly higher, at an average of 432.1 trees per hectare, than in the stands of type k (no treatment), at 309.5 trees per hectare. At an average of 362.6 trees per hectare, the density of the treated stands (type b) lies between the other two types, from which it is not however statistically different (Figure 5 bottom). The biggest differences with regard to stand structures - and thus obviously also with regard to habitat use by bats - are thus between the zero plots (high stem counts) and the non-treated plots (low stem counts).

To find out whether there are other factors besides the stem numbers that have a decisive influence on the diversity and activity of the bats on the surveyed plots, correlations between the species numbers or mean levels of activity in the survey period and the structural parameters determined at the batcorder sites were calculated. Of the many available structural parameters, only those where an influence on the diversity or activity of the bats seems conceivable were considered. Another factor included in the analyses was the parameter “treatment with plant protection products (yes/no)”, as this was of particular interest for the study.

When looking at the correlations between the selected parameters and the alpha diversity, it is striking that there is no correlation between the species numbers at the batcorder sites and the “treatment” factor. Significant positive correlations with alpha diversity can be demonstrated for the structural parameters “stand age”, “proportion of free ground” and “basal area per hectare”; significant negative correlations can be shown for the parameters “cover of the shrub layer” and “number of stems per hectare”.

There are similar correlations with regard to mean bat activity. As with alpha-diversity, the mean bat activity is not influenced by the use of plant protection products. Factors promoting activity (significant positive correlations) were the cover of the herbal layer and the mean breast height diameter (BHD), while the parameters “cover of the shrub layer”, “number of layers” and “number of stems per hectare” were found to inhibit activity (significant negative correlations). Overall, the diversity and activity of the bats on the sample plots under the given general conditions were thus obviously not influenced by treatment with MIMIC®, but rather by differently developed stand structures.

Discussion

More than almost any other forest type, oak and mixed oak forests are characterised by a high species diversity. They are therefore quite rightly called “hotspots” of biodiversity. This is also confirmed by the results of this study, in which the presence of 13 different bat species was unequivocally confirmed. This corresponds to more than half of the 22 species native to Bavaria. A comparably high number of twelve species was also found by Runkel (2008), during surveys of the bat fauna in the Ebrach forest enterprise.

Particularly special is the evidence showing the presence of the rare Alcathoe bat (Myotis alcathoe), which is categorised as “critically threatened” on both the Bavarian and the national Red Lists. It is all the more pleasing that this species showed the third highest total level of activity of all detected species and was documented in both study years as well as in all variants. In addition, there was a clear indication for one study area of the presence of a maternity roost in the immediate vicinity.

An influence of the use of pesticide on the diversity and activity of the bats was not observed. This was true even for the guild of Lepidoptera specialists, i.e. those species that specialise in butterflies as food. Overall, the forage supply for bats does not seem to have been significantly reduced by the treatment with MIMIC®. This is probably due in particular to the selective effect of the active ingredient tebufenozide in MIMIC® on free-feeding butterfly caterpillars, and the broad feeding spectrum of many bat species (ability to fall back on alternative food sources).

While there was no evidence that the pesticides had influenced the species numbers and activities on the sample plots, both positive and negative correlations with bat diversity or activity were detected for various structural parameters. High numbers of species and levels of activity tended to be found in older stands with low stem numbers. Furthermore, it could also be shown that the presence of a shrub layer or an increasing number of stand layers has a negative impact on activity and species richness. Generalising strongly, structures that restrict the flight space can thus be seen as more likely to reduce activity and diversity, while structures that facilitate flying and manoeuvring are more likely to promote activity and diversity. In addition, it can be assumed that the warmer climate within sparse stands has a positive effect on insect biomass and thus on the food supply. The greater attractiveness of older stands can possibly also be attributed to a greater supply of roosts. The great importance of stand structures for bat habitat suitability is also confirmed by other studies, in which the influences of stand density, stand age, stand height, vegetation stratification or crown cover on the activity of bats were also shown.

Summary

In order to protect the ecologically and economically valuable oak forests from large-scale mass propagation of pests and defoliation by feeding over extensive areas, areas particularly badly infested with the gypsy moth have sometimes in recent years been treated with the plant protection product MIMIC®. Until now, little was known about the effects of such plant protection measures on forest bats. The "Pilot study on bat activity in Middle and Lower Franconian mixed oak forest stands affected to different degrees by climate change” was carried out to at least reduce this lack of knowledge. No influence of the pesticide use was observed on the diversity and activity of the bats. Instead it was the structures of the stands that turned out to be decisive for bat habitat use.