«AA_WSL01» is written in blue on an inconspicuous fir tree in the «Rameren» forest in Birmensdorf near Zurich (fig. 1). The DNA for the first sequenced silver fir genome – the complete genetic material – was obtained from its seeds and needles. Worldwide, silver fir (Abies alba) is only the sixth conifer species whose genome sequence is known – which was quite a challenge as coniferous trees have an extremely large genome with many repeating, similar stretches of DNA sequence.

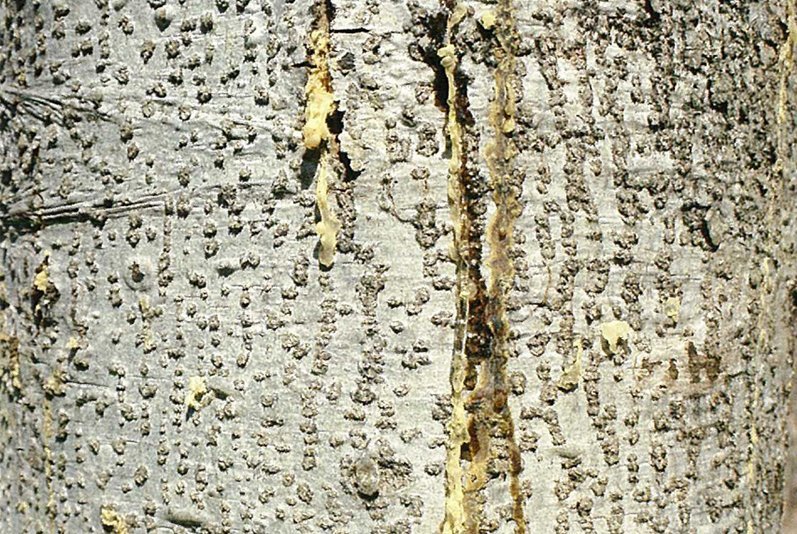

Fig. 1 - The first sequenced silver fir stands in a forest near Zurich and is a rather inconspicuous representative of its species. Photo: Christian Rellstab (WSL)

For this reason, this major task of sequencing it was only possible thanks to international cooperation. The research team decoded a total of 18 billion base pairs, the individual building blocks of DNA. That's six times more than in the human genome. Printed on paper, this would result in over 3.5 million A4 pages with 10-point Calibri font and 2 cm margins! It is not hard to imagine that this required very powerful computers and a long computing time.

"It's like a huge puzzle that you put together without a template", explains co-author Felix Gugerli of the WSL. Representing with his team the Swiss side of the international consortium, he commented, "We now have a comprehensive but slightly blurred picture of the silver fir genome." The parts of the genome that contain genes– that is, genetic information for the production of proteins with specific functions — are now well described. Between these parts, however, there are many repetitive sequences of base pairs. Much work still needs to be done by the researchers in order to arrange a complete picture from these pieces of the puzzle.

The right fir for every location

The effort is worthwhile, because a decoded genome helps to understand the genetic diversity within the species, for example, to describe which trees thrive particularly well at which sites. In addition, Christmas tree growers have an interest in selecting trees with desirable characteristics, such as long-lasting needles. Examining the genes of young plants makes it possible to establish their characteristics, so it is not necessary to wait until they have grown for several years. This is much quicker than carrying out costly planting trials.

Silver fir became popular in the 18th century as the Christmas tree par excellence until it was replaced by the longer-lasting Nordmann fir. As a result of climate change, silver fir is becoming increasingly important in silviculture as a substitute for the economically important spruce and beech. These species are less likely to thrive in a warmer and drier climate than fir. Compared to them, silver fir has been at a disadvantage because deer find its young shoots exceptionally tasty. As the deer population has been rapidly increasing due to a lack of natural enemies, these trees must often be protected by fences or plastic enclosures.

Fig. 2 - A magnificent silver fir in a mountain forest in Emmental, Switzerland. Photo: Markus Bolliger

The expensive and time-consuming cultivation of the silver fir is more worthwhile when foresters can select the optimal trees for the planned location thanks to genomic analyses. Indeed, forest management is already directing its practice towards converting even age spruce forests back to uneven aged mixed spruce, fir, beech forest. Thus, the decoding of the silver fir's giga-genome is an investment into the future of an important tree species and in sustainable forest management.