The pathogen causing hornbeam decline (Anthostoma decipiens) has been known in central Europe since the end of the 19th century, but was considered a rarely occurring deadwood decomposer. Since the 2000s, there has been increased damage to hornbeams in Italy in connection with this fungus, especially in public green areas. In Germany, the first evidence of Anthostoma was found on dying hornbeams in 2015, and in Austria it was detected in 2018 - in both cases at various locations in urban areas. Single cases in the forest followed in Switzerland in 2017, and in Saxony-Anhalt in 2019, both in fairly warm locations. The number of cases found in public green spaces has continued to grow, especially since the series of extremely hot and dry years from 2018 onwards. On the situation in the forest, there is little information so far. This prompted the Bavarian State Institute of Forestry (LWF) to carry out spot checks in warmer regions of Bavaria in order to get an impression of possible occurrences in the forest.

Symptoms

Typical for an infestation with the pathogen of Anthostoma hornbeam decline are the orange to deep red spore masses of the secondary fruit form Cytospora decipiens, formed mainly during the vegetation period, which emerge from the bark on the marginal areas of the infection (Fig. 2, 3). The black fruiting bodies of the main fruit form A. decipiens are subsequently formed in the necrotic areas (Fig. 6). The secondary fruit form can however also be formed again on already dead sections, and parallel to the main fruit form.

The fungus is able to colonise sapwood and heartwood, leading over time to a progressive loss of vitality in the tree, which becomes apparent in crown dieback and bark lesions and, in the case of heavy infestation, causes the death of the tree. Spore deposits of the fungus were usually found at forest edges or in stands with a lot of light, but there was also evidence of it in closed-canopy stands and on trees and areas of trunks not directly exposed to the sun. These were often related to damage that served as an entry point for the fungus. However, fresh fruiting bodies were also observed on undamaged parts of the trunk.

Both spore forms, but especially the main fruit form, A. decipiens, were frequently observed on standing and lying deadwood or deadwood broken out of crowns. The extensive occurrence of both spore forms could also be observed on trees with completely green crowns, as the infections spread more vertically (along the trunk axis) than horizontally, and the proportion of the trunk that is living is initially still large.

A. decipiens is capable of producing white rot, not only on deadwood, but also on trees that are still alive. This penetrates to the core of the tree in a wedge shape. In the active white rot infection zone of an infected hornbeam in Munich, the fungus could be detected on all 6 sampled cross-sections of the trunk and branches (Fig. 4).

Risk of confusion

The fungus Endothiella carpinicola also occurs in connection with hornbeam decline. However, it is considered to be far less aggressive. It was also detected in one of the stands in which A. decipiens was found. E. carpinicola can easily be confused with Cytospora decipiens, the secondary fruit form of Anthostoma. The spore deposits of E. carpinicola are lighter-coloured and emerge from the bark as droplets and in thin tendrils.

However, these can be washed out by moisture. For the same reason, there is a risk of confusion after rain with the deadwood decomposer Libertella betulina, which also forms yellowy-orange spore tendrils. In contrast to these two fungi, C.decipiens is more compact and less liable to be washed off by water. When dry, it is very tough and deep red in colour; the colour may lighten after rain. In cases of doubt, microscopic identification is essential.

The main fruit forms of A. decipiens should also be identified microscopically. Older spore deposits can be confused with Diatrype stigma (common tarcrust fungus) or Diatrypella verruciformis, which had also colonised the trees sampled here.

Anthostoma decipiens, however, is characterised by the elongated appendages of the fruiting bodies, which have a furrowed surface and are round when viewed from above (Fig. 5).

Weakness-exploiting parasites such as Diplodia mutila (bark blight) and Neonectria coccinea (red blister fungus) were also found on trees with hornbeam bark necroses or on other hornbeams in the same stand. As the damage progressed, the white rot pathogen Schizophyllum commune (split gill fungus) was often found.

Background to the search

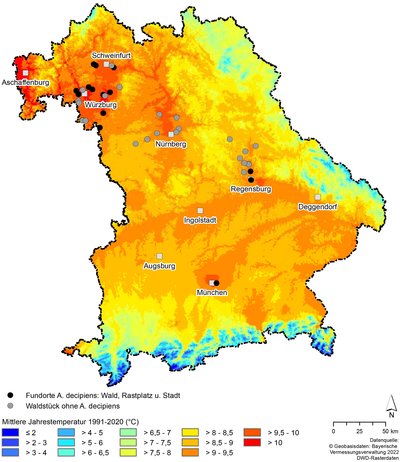

In autumn 2021, a chance discovery of Anthostoma hornbeam decline was made at a motorway rest area on the southern edge of the Franconian Plateau in Lower Franconia. This region around Würzburg is the warmest and driest in Bavaria. The discovery led to a total of 32 stands with larger proportions of hornbeam being surveyed there and in two other warm regions of Bavaria, around Regensburg and Nuremberg. No suspected cases were found around Regensburg and Nuremberg. The vitality of the trees there was obviously better than that of the hornbeams around Würzburg. On the Franconian Plateau, however, the fungus was detected in 8 of the 17 stands surveyed (Fig. 1). Additional findings at 3 of 7 inspected motorway rest areas with hornbeams in the area of the Franconian Plateau confirm that the pathogen occurs at sites where the trees are subject to stress. At one site, at least one third of the approximately two dozen trees was infected and already displayed spore deposits of A. decipiens and extensive necroses on the trunk. At a motorway rest area north of Regensburg, the disease was detected on a single, badly damaged hornbeam. However, further checks of hornbeams at 31 motorway rest areas around Regensburg were negative.

Recommended action

As little is known about the infection pathways and the spread of the fungus through the area, but also in the trees themselves, no firm recommendations for action can be given at this stage. Trees that already show symptoms on the trunk can in all likelihood no longer recover, and will generally die. It is uncertain whether the removal of infected trees can protect neighbouring trees from infection. As the cases detected in the forest have so far been limited to the hottest and driest region of Bavaria and sites in public green spaces, it seems that a loss of vitality in the plant and conditions conducive to the fungus are necessary for an outbreak of the disease. The future risk potential thus appears to be closely linked to the continued occurrence of climatic extremes. There could thus be significant damage on a localised basis. From today's perspective, however, an epidemic spread of the disease is unlikely. In general, however, anything that ensures a cool climate within the stand is conducive to preventing damage.

Outlook

An increased occurrence of Anthostoma as a parasite was observed in the aftermath of the extreme years from 2018, especially at sites where the trees are subject to stress. How the damage potential will develop in the future is difficult to estimate at this point in time. However, assuming there will be an increase in extreme weather events and a shift in site suitability, a fundamental increase in the occurrence of hornbeam decline seems likely.

Based on evidence gathered up to now, the host range of A. decipiens in the forest seems to be limited to hornbeam. Infection tests have shown not only successful colonisation of hazel bushes (Corylus avellana), but also a great potential for damage to the European hop-hornbeam (Ostrya carpinifolia). Other tree species such as black alder (Alnus glutinosa), silver birch (Betula pendula) and common beech (Fagus sylvatica) could be colonised, but the infections hardly spread.